AI workloads challenge the cattle model

AI workloads break the “cattle” 1 approach to infrastructure management that made Kubernetes an effective IaaS platform. Kubernetes stays agnostic of the workloads, treats resources as fungible, and the entire stack underneath plays along: nodes on top of undifferentiated VMs on undifferentiated cloud infrastructure. It’s cattle all the way down.

But AI infrastructure punishes mental models applied from inertia. Generic abstractions that worked for backend services are too limited, and treating six-figure hardware as disposable, undifferentiated cattle seems unacceptable.

Restarts

Take restarts. Software engineers learn to design and expect systems where the impact of a restart should be insignificant. In a generic backend service (an API, a stream processor) this works because a restart means dropping a tiny fraction of requests. For most AI workloads, the impact is a much bigger deal.

This is because AI workloads have fundamentally different constraints and different Service Level Objectives (SLOs).

Training workloads extend over long periods of time (anywhere from hours to weeks or months) and follow a regular pattern alternating in-GPU computation for individual batches with bursts of huge data exchanges during which participating GPUs synchronize gradients, perform checkpoints, etc. So a Pod dying mid-batch means re-computing and re-synchronizing that work.

This breaks expectations. Training workloads ultimately must optimize for speed and cost. Given that training a model locks a lot of expensive equipment for a long time, the priority is to maximize GPU utilisation. Even a modest rate of Pod restarts will have a massive impact on the overall cost, as a single pod restart may easily lead to repeating more work across all GPUs. That multiplier factor doesn’t exist in backend services.

Inference workloads are short lived in comparison to training, but still much longer than the typical request to a backend service (a chatbot might need seconds or minutes to reply to a prompt). And SLOs are very nuanced depending on the specific type of inference and use case. A chatbot needs to keep Time To First Token (TTFT) well under a second, so a Pod restart degrades the user experience. After the first token, the rest just need to keep a stable enough Time Per Output Token (TPOT) to keep up with the user’s reading speed. But for an LLM summarizing large bodies of text, or a vision model categorizing images, TTFT will be unimportant compared to overall throughput.

Topology awareness

When a traditional workload requests a particular amount of resources, the Kubernetes scheduler generally cares about finding available memory and CPU, but not much about where they are. With GPU infrastructure this changes.

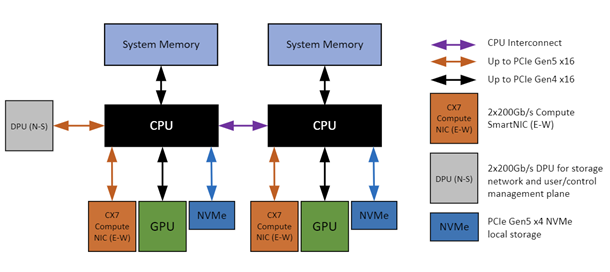

Topology awareness and node identity are critical factors for AI workloads. Training requires moving large amounts of data efficiently across all participating GPUs, and those transfers happen through many communication paths across the network fabric, and within individual servers. To support these needs, a low-end GPU server might look like this (NVIDIA-Certified Systems Configuration Guide):

But paying for the more expensive equipment is not enough if the scheduler doesn’t leverage it correctly.

Imagine two of training jobs, A and B, and each requests 2 GPUs. If

task A gets the two GPUs on the left, and B the two on the right, a

gradient synchronization stays within a single CPU socket making data

transfers efficient (50-55 GB/s on Gen

5).

But if A and B get one GPU on each side, traffic will be forced to

traverse the CPU interconnect, reducing bandwidth by

3-4x

and creating unnecessary contention. All for a scheduling decision that

Kubernetes doesn’t even know exists.

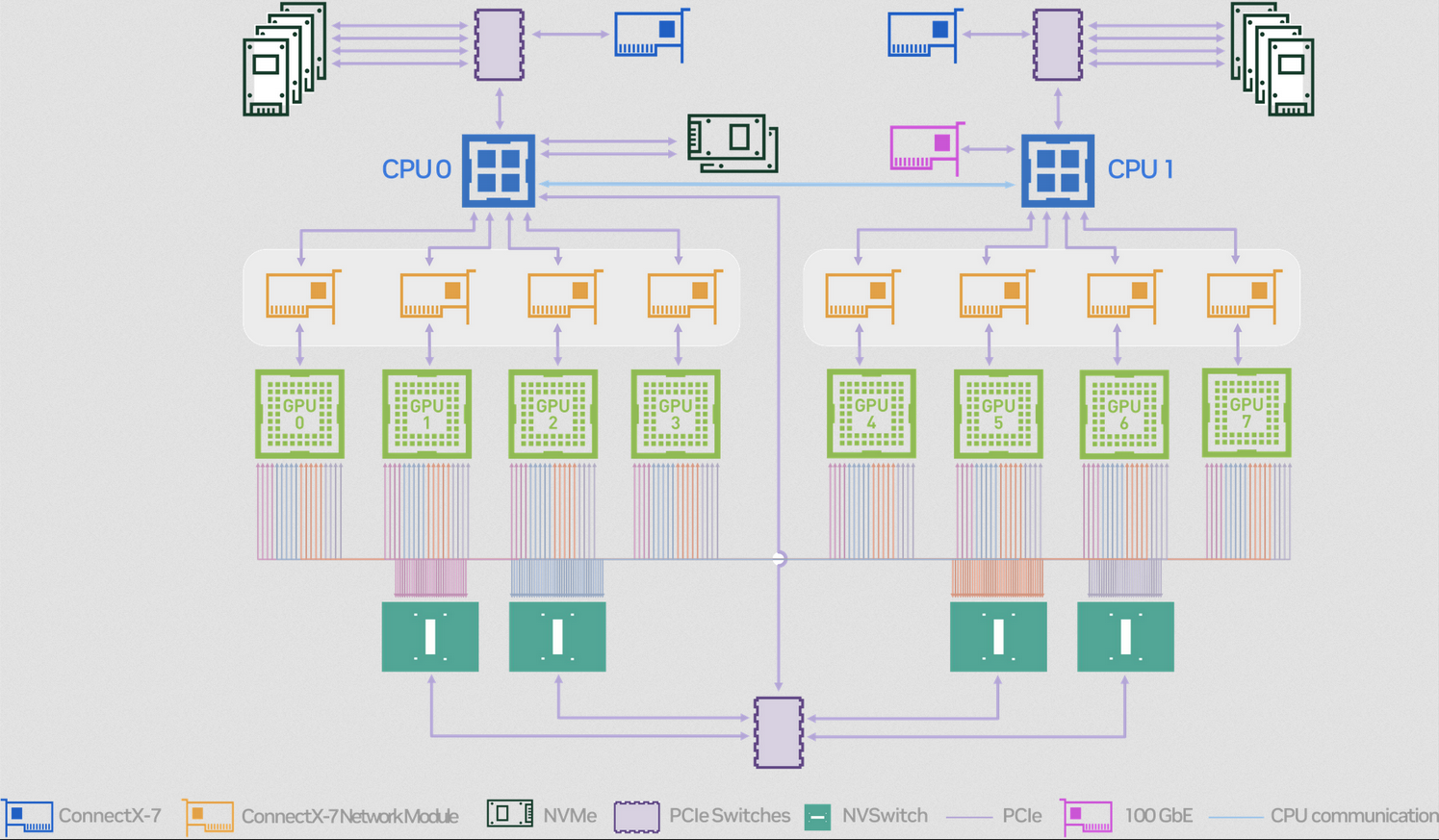

Higher-end servers scale the number of GPUs making the topology more complex and scheduling decisions more nuanced. And at the top of the spectrum, servers add direct GPU-to-GPU interconnects, dedicated high-bandwidth NICs (giving each GPU a dedicated bandwidth of 400 Gbps), and optimized topologies. The diagram below shows how NVIDIA’s DGX H100 (a pre-assembled server) creates a full mesh topology directly via NVLink.

The scheduling problem becomes much harder than traditional clusters. It is no longer about “find an available host with this much memory and CPU”. When managing AI workloads, the exact placement matters at every level, the GPU itself, but also which NUMA node, which PCIe switch or NVSwitch configuration, which NIC, etc. Once we add multiple servers, we will also have to worry about the deep rabbit hole of high-performance networks.

Kubernetes has no native understanding of most of these details, so it relies on the operator supplying that information up front by configuration or other means.

The NVIDIA GPU

operator

helps by exposing GPU topology information to the Kubernetes scheduler.

It uses lower level tools (e.g. nvidia-smi) to extract information

about GPU placement, interconnects and NUMA domains, which enable better

scheduling decisions. The operator also provides a Kubernetes device

plugin

so that workloads can specify new resources, this example Pod

spec

is requests 1 GPU:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: cuda-vectoradd

spec:

restartPolicy: OnFailure

containers:

- name: vectoradd

image: nvidia/samples:vectoradd-cuda11.2.1

resources:

limits:

nvidia.com/gpu: 1

From the user’s perspective this is deceptively simple, but it still depends on the operator having configured node pools correctly based on the specific server and GPU types, etc.

Resource selection

The cattle model lets users think of resources in terms of high-level abstractions like “cpu share” or “memory size”. Those categories are too coarse if we’re dealing with GPU infrastructure.

For example, the nvidia.com/gpu resource

shown above refers to a full GPUs. But some AI workloads may be too

small (e.g. a Jupyter notebook), so reserving that much compute is a

waste. To avoid this, cluster operators can partition GPUs using

features like multi-instance GPU

(MiG),

which allows exposing a GPU as smaller GPU instances.

For example, the NVIDIA

A100

supports a profiles like 1g.5gB (exposing 7 GPU instances to the host

with 1/8th of memory each) or 3g.30gb (3 GPU instances with 4/8th of

memory). With the NVIDIA Operator, those MiG partitions appear as

resource types. A user running a workload can then adjust resource

allocation to request MiG instances and avoid taking larger GPUs unless

it’s necessary.

[...]

resources:

limits:

nvidia.com/mig-3g.30gb: 2

But this also implies that users cannot simply throw workloads to the cluster assuming that the cluster has a herd of undifferentiated “GPU units” as they would with CPUs. There is an abstraction leakage: users need to think about GPU partitioning, memory slices, and operator-level concerns much deeper than in traditional backends.

Heterogeneous clusters

The need to adapt infrastructure to the combination of workloads that make sense for each organization is a key factor why heterogeneous clusters make sense in this context.

Consider for example disaggregated inference. This technique is used to improve performance in LLM engines based on the SLOs mentioned above. To handle a request, the engine will split the work in a “Prefill” phase that optimizes for TTFT, and a “Decode” phase that optimizes for TPOT. Both phases have very different constraints: prefill is in charge of the initial processing of the prompt and is very compute intensive, whereas “Decode” is less compute and more memory intensive. So it might make sense to have a heterogeneous cluster that dedicates higher-end GPU servers with NVLink for prefill, and less powerful GPUs with more memory for decode.

In this scenario, you probably also want to reserve high-end nodes for Prefill even if the GPUs are idle to ensure that incoming requests achieve better TTFT. This trade-off, intentionally keeping expensive resources underutilized, is not exactly what the Kubernetes scheduler is designed to do.

Are pets back then?

No. The complexity and scale of AI infrastructure makes a cattle approach mandatory. But to keep applying it, we need to extend the capabilities of our tools to fill gaps as they appear.

Schedulers like Volcano or NVIDIA’s

KAI extend Kubernetes with

topology awareness and more sophisticated scheduling policies that help

make effective and efficient use of expensive resources (some like gang

scheduling making their way into k8s). Distributed application

frameworks like Ray can build on top, provide

users with higher level abstractions tailored for AI workloads (e.g. the

kube-ray

operator

adds custom resources like the RayCluster for training jobs, or the

RayService for inference use cases), and manage their lifecycle more

effectively.

This preserves the core principles of the cattle model: we isolate the complexity of infrastructure behind general purpose abstractions with just enough knowledge of the workloads that run on top, and allow users to submit work that runs effectively without the need to dig in lower level details.

The cost comes as more layers of complexity that require operators with expertise in GPU architectures, PCIe topologies, network fabrics, and virtualization, and users with enough technical knowledge to understand how to translate their constraints and SLOs to infrastructure requirements.

Footnotes

[1][]: The “pets versus cattle” metaphor contrasts two ways of managing

infrastructure. In the old days, we treated each piece of hardware as

pets, special, unique, with server names like Gandalf (sticker

included), their very own IP address and configuration. Should it break

it was a Big Deal to replace with its successor Legolas, Gimli, or

whatever fit our naming schema [2]. Under the cattle mindset, resources

are just anonymous, indistinguishable resources. When Pod 4baad43

dies, the Kubernetes scheduler shrugs and spawns 23f13ca.

[2][]: Naming schemes seemed notably unimaginative: Lord of the Rings characters, constellations, metal bands… Some of the last.fm servers were a notable exception, but the naming scheme shall remain in the dark.

Any thoughts? send me an email!

To get notified on new posts, follow me on Bluesky / Twitter, or subscribe via RSS feed or email:

Archive

- Inferencing delivery bottlenecks away

- Code reviews can't keep up

- AI workloads challenge the cattle model

- PoC is a framework of perverse incentives

- AI-generated code will choke delivery pipelines

- Why aren't we all serverless yet?

- Identifiers are better off without meaning

- Alert on symptoms, not causes

- How about we forget the concept of test types?

- How organisations cripple engineering teams with good intentions

- Migrating an Eureka-based microservice fleet to Kubernetes

- ⭐ Talk write-up: "How to build a PaaS for 1500 engineers"

- ⭐ Kubernetes made my latency 10x higher

- Sizing Kubernetes pods for JVM apps without fearing the OOM Killer

- GC forensics by example: multi-second pauses and allocation pressure

- ⭐ How does the default hashCode() work?

- Frugal memory management on the JVM (Meetup)

- DirectBuffer creation / disposal has hidden contention on sun.misc.Cleaner